What if there was a simple way to share the spoils of Big Tech with the people whose jobs it replaces?

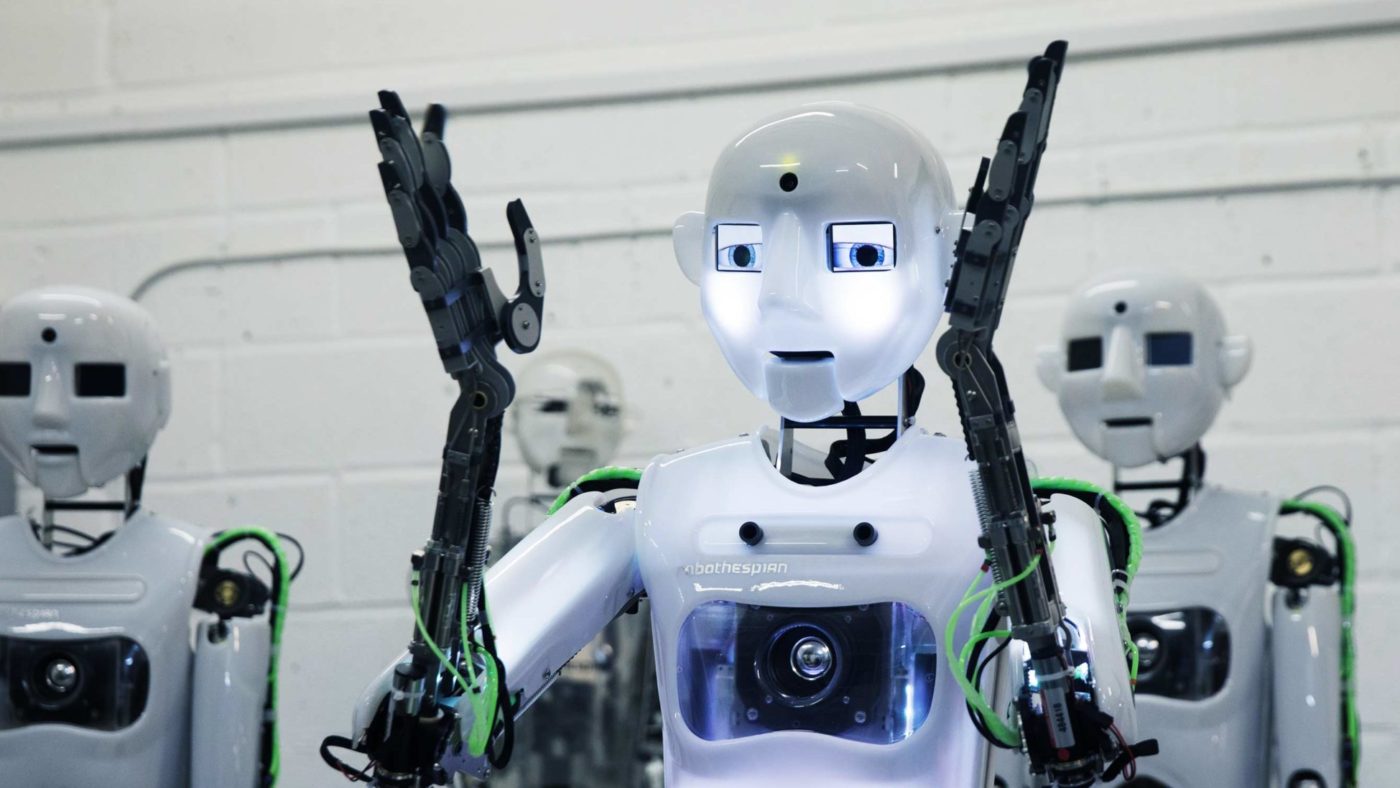

That this replacement is happening is beyond doubt. Daniel Susskind’s excellent new book, A World Without Work, and, to a lesser extent, Carl Benedict Frey’s The Technology Trap, both discuss the way not only robots, but also artificial intelligence, are slowly but surely encroaching on the whole spectrum of employment.

Technology has no doubt enhanced the volume of work an individual can do thereby increasing the size of the economic pie which we share. But it has also meant that plenty of jobs traditionally done by humans are now surplus to requirements. Of course, those technologies often create new jobs of their own, either managing or serving the machine, or in whole new sectors that don’t even exist yet.

However, both authors do point out that modern technologies are often better than humans at the same task and, as the title of Susskind’s book alludes, there is a direction of travel whereby machines and computers eventually do all the work that needs doing. The doomsday scenarion is that the owners of the machines will receive all the income generated by those machines leaving a large number of humans with no way of getting a slice of the economic pie.

My suggested solution for this dilemma is a Norwegian-style sovereign fund to try and capture the gains of new technology, whilst alleviating some of the economic shocks.

The revenue from such a fund could begin to replace some of the income tax that a gradually less employed populace would pay to the state meaning that essential services like the health service and police or – given the potential volume of leisure time created by that much unemployment – education, could continue to be funded on a cost-neutral basis. If the fund is big enough, income tax, and even other taxes, could be rolled back.

Government is currently trying to find ways to claw back lost revenue from “missing” corporation tax from big technology companies. Perhaps the simplest way to do this would be to invest in them and receive the dividends instead.

Investing directly would be far better than the way government goes about things now. Schemes like the Faraday challenge, encourage companies to chase government mandated aims in order to potentially win a prize. Other schemes encourage cross-industry collaborations with the promise of part-funded research and development costs.

These seem unnecessarily complicated. In many cases, companies need scale to demonstrate a benefit to the taxpayer meaning small start-ups and new technology companies are automatically excluded. By directly investing in a range of start-ups, the government may mis-spend a few times over (like most venture capitalists), but the overall benefit will be greater as companies can spend the resource on what they think best, not trying to hit a government-mandated target.

One of the big complaints from start-ups in the continent of Europe is that venture capitalists all hang around in Silicon Valley and start-up capital is hard to come by this side of the Atlantic. Government bridging that gap would firstly provide the seed capital, but secondly provide a signal to the market that these kinds of speculative investments are a good use of resources. This would also generate network effects, like in Silicon Valley, whereby companies locate into the UK in order to tap into the highly educated (but potentially underemployed) workforce and the available no-strings-attached government funding.

Finally – and this is what may make this more attractive to the current government – EU rules on State Aid would probably forbid such an investment (or, at the least, make it really complicated to do). Post-transition period, there need be no such brake.

Of course, there are some risks. The taxpayer would be heavily invested in these companies which may create conflicts of interests later on or it could even create its own market distortions. These are obstacles to overcome and risks to mitigate. However, I don’t believe these risks outweigh the benefits or that these aren’t already issues across various sectors such as defence or construction where government procurement is the main driver of market activity.

The world of work is changing and there are few ways left to try and prevent the social upheavals that might be caused by the capture of all the benefits from capital. A Sovereign Tech Fund may be the simplest and most direct way to capture those benefits for the benefit of all.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.