Along with my Cato Institute colleague, the economist Daniel Mitchell, I spent the last weekend in Prague, at the annual meeting of the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists. The AECR is comprised of European political parties that are committed to “individual liberty, national sovereignty, parliamentary democracy, the rule of law, private property, low taxes, sound money, free trade, open competition, and the devolution of power”.

It was a pleasure to see the principles advanced by Cato alive and well on the other side of the Atlantic, and share the stage with principled promoters of freedom, including the British Conservative MEP Daniel Hannan.

Whether by chance or design, the AECR conference was the perfect antidote to the recent summit of European Union heads of state, which took place at the same time in the Slovak capital of Bratislava. Slovakia currently holds the six-month-long rotating presidency of the EU. This was the first meeting of the EU’s great and the good since the British referendum on membership in the EU. As such, it lacked the presence of British prime minister Theresa May. No doubt she was devastated.

I raise the issue of the two meetings because the former was devoted to finding a way out of Europe’s multitude of problems – low growth and high unemployment, persistent tensions between the winners and losers in the eurozone, rising discontent and growing support for “populist” parties, and the mishandling of mass migration from North Africa and the Middle East.

The latter was a predictably bland and forgettable gathering that called for, as you might expect, “more Europe” and ended with an explicit commitment from the Slovak prime minister Robert Fico to making the British withdrawal from the EU as painful as possible.

So, as a public service, allow me to elucidate Fico’s character – and thereby try to alleviate some of the residual concern that part of the British populace still feels about the wisdom of leaving the EU.

Were he living in a country with an independent judiciary, Fico would possibly be serving time, not issuing threats to a country that has given the world the rule of law. It is only thanks to the amplifying force of the disintegrating EU that a man who, via the miracle of coalition politics, gets to lead a country of 5.5 million souls, feels able to threaten 65 million Britons.

Fico’s hissy fit over Brexit is, in fact, a sign of weakness, not of strength. Great Britain, and to some extent Germany, have been soaking up Slovakia’s excess labour for years. Indeed, it is precisely Fico’s failure to create a strong economy – he has led Slovakia, on and off, for a decade – that has led tens of thousands of Slovakia’s best and brightest to leave that country and start anew in Britain.

There is a certain method to Fico’s madness, in other words. He needs Britain to do what he has failed to accomplish – create a business environment that will allow his people to get jobs. And so, in return for lenient terms regarding the British withdrawal from the EU, he hopes to preserve the freedom of movement that keeps unemployment in Slovakia slightly below 10 per cent.

For EU leaders in Poland and the Baltic, it is not only the employment market that matters: they want to make sure Britain, even if it leaves the EU, remains firmly committed to their defence against Russian revanchism. But Fico is a Russophile. He does not fear Putin’s territorial ambitions: indeed, he is opposed to the sanctions imposed on Russia for invading Ukraine. (This attitude is shared by parts of the Czech political establishment, probably because that country is even further from Russia).

For Fico, the EU summit came at the best possible moment, since it took the media’s focus off a massive corruption scandal that threatened to engulf his administration.

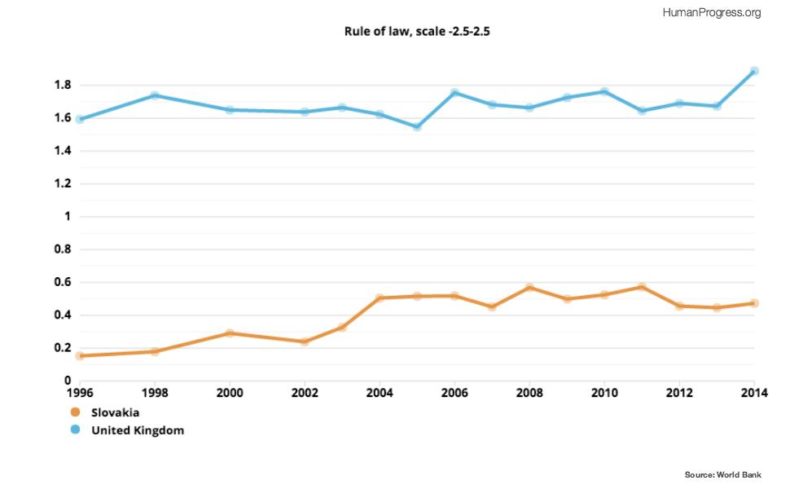

The gist of the story is as follows. A well-known Slovak real estate developer, Ladislav Basternak, stands accused of a massive tax evasion scheme – flipping a large number of properties in some of Bratislava’s swankiest suburbs over a number of years without the payment of capital gains tax. (A symptom of a more general problem, as this chart shows, with the country’s political culture.)

When the tax authorities finally caught up with Basternak, he signed over some of his companies to Fico’s close friend and minister of the interior, Robert Kalinak, who oversees the Slovak police. It goes without saying that Basternak was never prosecuted for tax avoidance.

When a whistleblower leaked bank information that tied Kalinak and Basternak together, Fico refused to fire the former and appointed a prosecutor to investigate the latter. As was quickly discovered, however, the supposedly independent prosecutor lives in a luxurious condominium owned by Basternak – as does Fico himself. Indeed, the premier’s financial disclosure forms indicate that his rent is roughly 75 percent lower than would be the case for a similar property.

Put another way, Slovakia’s prime minister appears to be enjoying close-to-rent-free living in return for protecting his landlord from prosecution.

The proper response to Fico, in other words, is not fear, but contempt. And such a man is given a platform by the European Union to threaten Britain – and even a potential veto over the terms of its Brexit deal – suggests quite how sensible your country was to get out while it had the chance.