The government has released a policy statement outlining, in broad strokes, what its new points-based immigration system, due to come into effect next year, is going to look like.

As anticipated, the biggest change is that freedom of movement for people from the European Economic Area (plus Switzerland) will definitely come to an end. This is, in my view, a huge mistake. It means getting rid of the most successful branch of our immigration system, a branch which is wonderfully unbureaucratic, cost-effective, and which offers a remarkably high degree of legal certainty. But then – this is not exactly news. We knew that free movement was going to end, so this was already priced in.

That aside, there is much to commend in the paper. For a start, the pointless cap on the number of skilled work visas is going to be dropped, as plenty of economists (myself included) have advocated. It was thanks to the visa cap that thousands of medical professionals, IT specialists, scientists and engineers had to be turned away. This is terrible economics, but it is not even good politics, because all the surveys show that highly skilled migrants are popular in Britain – even among people who claim to be hostile to “immigration” in the abstract.

The so-called “Resident Labour Market Test”, which stipulates that a job has to be advertised domestically first, and can only be given to an immigrant if no suitable UK applicant can be found, will also be scrapped. This was, in practice, a superfluous, time-consuming box-ticking exercise, and it could not have been anything else – because how are you going to prove that an employer was genuinely trying to find a British candidate?

The minimum skills threshold and the minimum salary threshold are also going to be dropped. At the moment, if you want to move to Britain, you must have at least an undergraduate degree (or a vocational equivalent), and an offer for a job which pays at least £30,000 a year. From next year on upper secondary education – equivalent to A-Levels – and a salary offer of £25,600 will suffice. Since a lot of jobs in Britain are in that skills range and earnings range, this represents a substantial liberalisation of the immigration system for a lot of non-Europeans.

On the minus side, the new system will close off most legal routes for low-skilled migration. It is based on the popular, but wrongheaded idea that only skilled migration is desirable, while low-skilled and unskilled migrants are a drain on the economy. The Government sees this new system as part of an effort to create what they describe as “a high wage, high-skill, high productivity economy”, which sounds rather like a motherhood-and-apple-pie statement. Who could be against that?

Me, for a start. Imagine an economy with only two professions, hedge fund managers and patent lawyers. This would undoubtedly be a high-wage, high-skill, high-productivity economy. But it would also be a rather dull place to live, because there would not be much to do, leisure-wise. Now imagine a group of unskilled migrants moved to that place, to open pubs, restaurants, cafes, hotels, clubs etc, and work in them. The hedge fund managers and the patent lawyers would still be as productive as they were before. But the average wage, the average skill level, and the overall productivity level of this economy would now be lower. Shutting out low-skilled migrants may improve some macroeconomic aggregates, but it will not make Britain a better place to live.

There are ways around the cap. For migrants whose occupation is on a shortage list, the salary cap drops to £20,480. But this does not really solve the problem, because the definition of a “shortage” is rather arbitrary.

Put it this way. Almost nobody in Britain speaks Icelandic, but we would not say that we have a “shortage” of Icelandic-speakers. The reason is simple. If you thought about setting up a business which could not function without Icelandic-speaking employees (say, a translation service), you would just not set it up in Britain. A shortage implies unmet demand – somebody is looking for a skill, but unable to find it. But if you already know that a skill is not available, you may not bother looking for it in the first place.

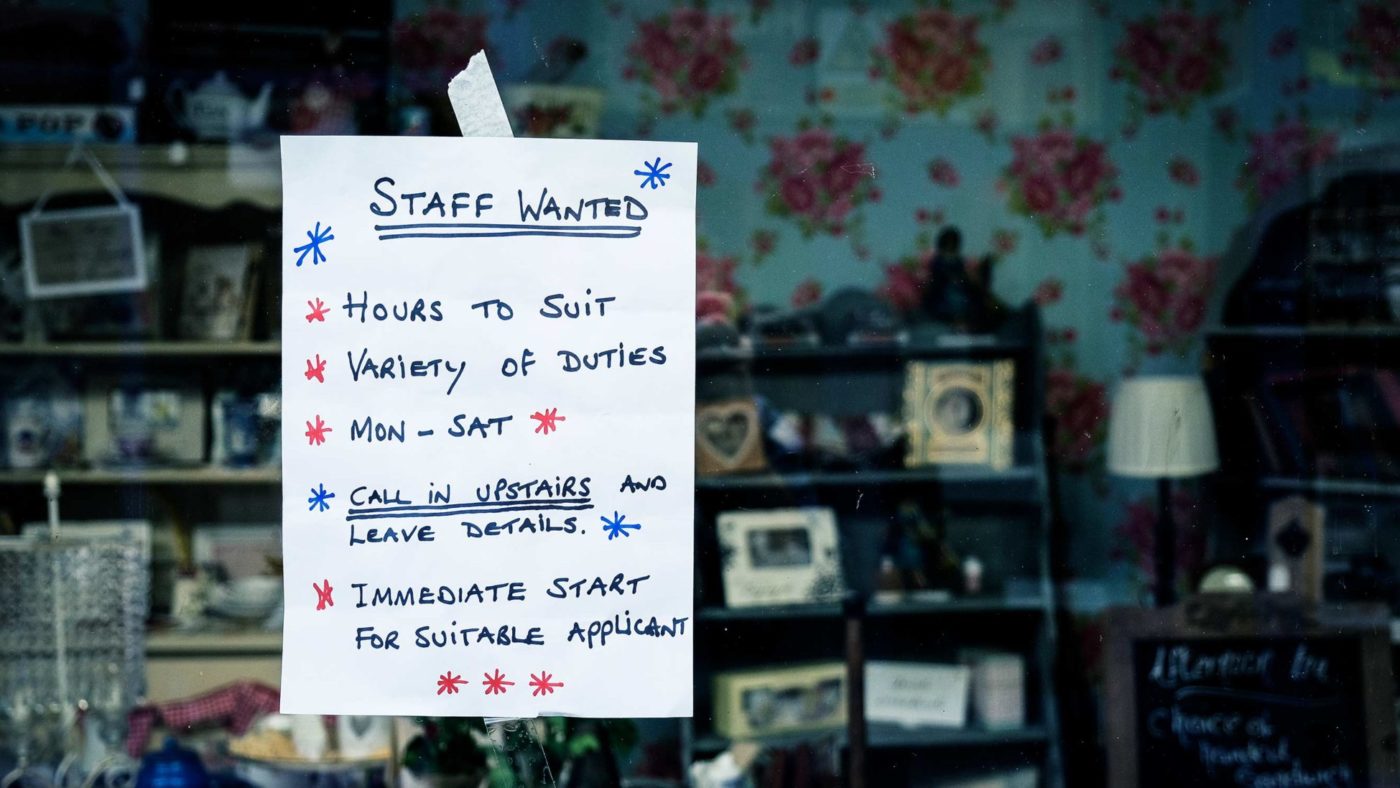

In the same way, post-Brexit Britain will not be a place with “Staff urgently needed” signs in the window of every pub, every shop and every restaurant. It will, most likely, just be a place with fewer pubs, fewer shops and fewer restaurants.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.