Oxfam’s latest annual report states that the richest one per cent owns wealth that is equivalent to that of the rest of the world combined. The report goes further by asserting that just 62 individuals have the same wealth as 3.6 billion people in the “bottom half of humanity”. The Independent newspaper claimed the report’s conclusion “is the result of a system which allows the rich unfettered representation without taxation.”

It is welcome that the issue of global poverty is again being put in the spotlight. Despite major falls in absolute poverty over previous decades, a great deal more needs to be done to help the world’s poorest. However, the claims on global inequality in Oxfam’s report are misleading. Oxfam is using data from Credit Suisse’s Global Wealth Report 2015, which calculates wealth based on the present value of all assets minus debts. This methodology of calculating wealth produces some strange results, including:

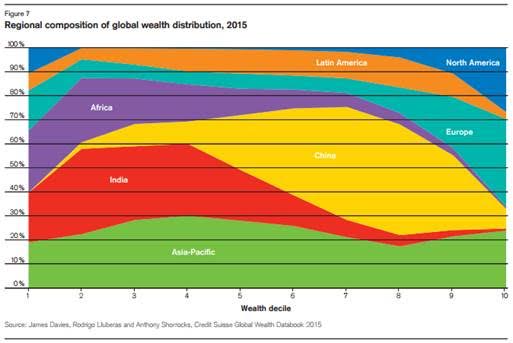

- 10 per cent of the world’s poorest reside in America and around 20 per cent of the world’s poorest reside in Europe, but virtually none of the world’s poorest live in China (See figure 1).

- A young investment banker with student debts is deemed one of the poorest people in the world. However, a rural farmer in India with minimal savings is considered richer than the young investment banker.

- Once debts have been subtracted, a person needs only $3,210 to be among the wealthiest half of world citizens.

Figure 1: Regional Composition of Global Wealth Distribution (2015)

Source: Credit Suisse – Global Wealth Report 2015 link

The people in the US and Europe in the bottom of the world’s population – according to the Credit Suisse wealth measure – are simply those with more debts than assets. These will include many students and mortgage holders, who face absolutely no poverty whatsoever. In fact, as Ben Southwood from the Adam Smith Institute points out, having negative wealth may actually be a sign of prosperity, since only people with good financial prospects can secure loans. The debts of these groups will also drag down the overall wealth figure for the bottom 50 per cent of the distribution, making a wealth comparison of this group to the richest in society misleading.

Despite the problems with the wealth methodology used by Oxfam, the report does address some important issues. It emphasises the progress that’s been made in eliminating absolute poverty. They point out that the number of people living below the poverty line has halved between 1990 and 2010, and they present analysis showing that all groups have received an income boost since 1988. There are also some interesting facts in the report that should be of concern. For example, it is estimated that almost a third of rich Africans’ wealth – a total of $500bn – is held in offshore tax havens, costing African countries $14bn a year in lost tax revenues.

These are important points that deserve far more attention.