“The free market economic model has failed. Trickle down didn’t happen.”

Just the sort of tubthumping rhetoric you would expect from the hard left of the Labour Party.

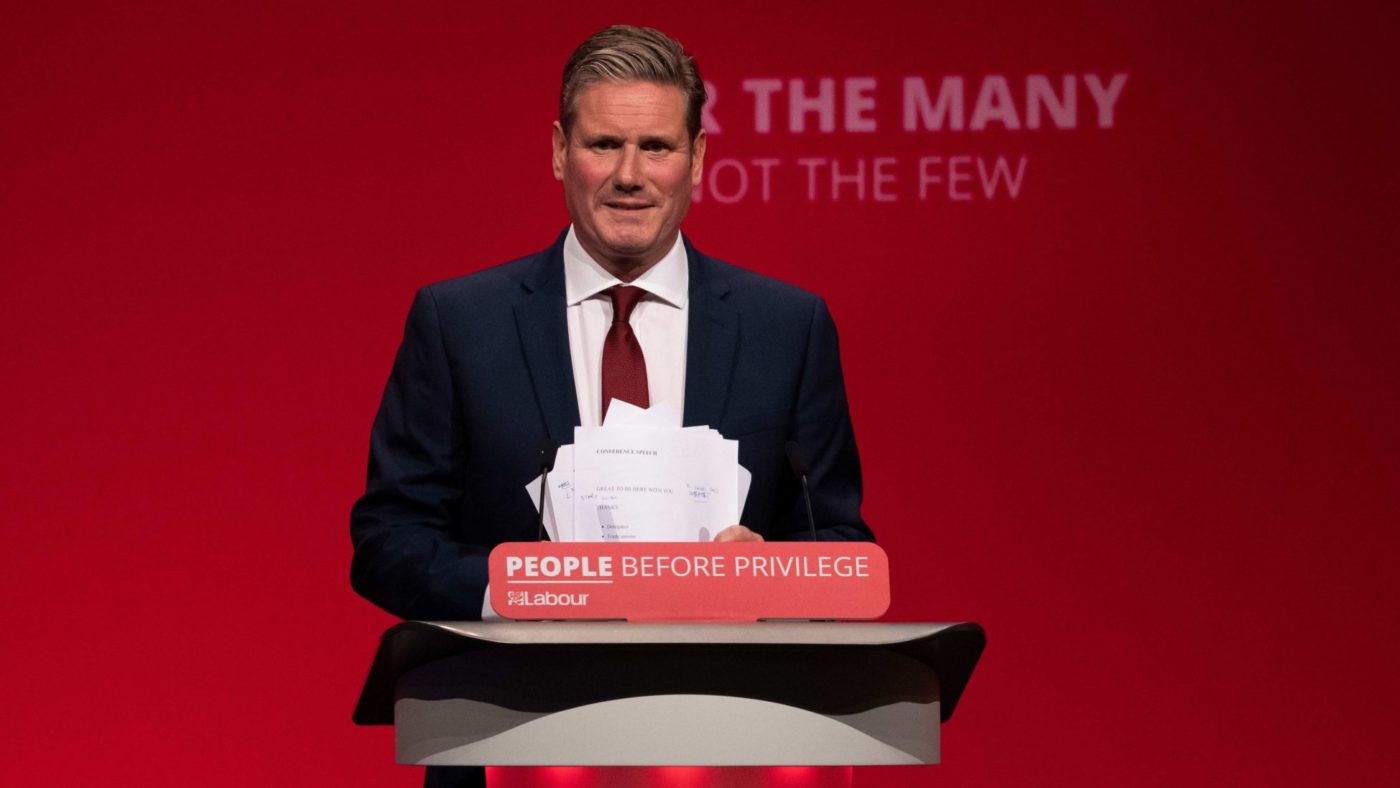

Except, in this case, these were the words not of Jeremy Corbyn or John McDonnell, but Sir Keir Starmer, the mild-mannered lawyer who many expect to become Labour’s next leader.

It’s not all that surprising to hear the former prosecutor employing this kind of rhetoric in a Labour leadership contest. After all, this isn’t a general election – he’s trying to appeal to an electorate that is considerably more leftwing than the general public. Painting himself in deepest red makes strategic sense, as does his care not to repudiate the Corbyn project.

Whether or not Mr Starmer’s approach so far reflects his deepest held political convictions is difficult to say – though it would hardly be a surprise if the former barrister tacks to the centre if he does become leader.

What is trickle down?

All that being as it may, it is still worth interrogating that claim about ‘trickle down’, as it remains an infuriatingly common leftwing trope about free market economics. Briefly put, it suggests that rightwingers want to cut taxes for the wealthy in the hope they will spend more money and that will filter down all the to the rest of us.

It’s an idea with a considerable vintage. Indeed, you can see a version as far back as the 1896 presidential election, when the Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan characterised his opponents’ position as “if you just legislate to make the well-to-do prosperous…prosperity will leak through on those below”. (That was not just an attack on the Republicans, incidentally, but also on the conservative Bourbon Democrats).

The problem is that idea of ‘trickle down’ is little more than a straw man, an unfaithful representation of the tenets of free market economics. As CapX contributor Jamie Whyte put it recently, the likes of Adam Smith, Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman never advocated anything resembling trickle down.

Arguing for less burdensome regulation, lower taxes and a smaller state is about creating a more efficient, dynamic economy with more opportunity, competition and innovation.

Or to put it more simply, it’s about promoting economic growth, whose benefits are felt not only in more jobs and lower prices, but also in more revenue for public services and redistribution to those in need – none of that has much to do with wealth ‘trickling down’ from the wealthy.

Nor are the policies favoured by free marketeers here in the UK particularly focused on alleviating the tax burden of the already well-off. When it comes to tax policy they are much more likely to focus on, say, the iniquities of stamp duty, the way stingy allowances disincentives business investment, or our hopelessly wonky consumption taxes. Those reforms are all about creating a more coherent, growth-enhancing tax system, not offering bungs to the wealthy.

Throughout his leadership, Jeremy Corbyn has tended to lump business in with high-income individuals as one big rich blob – and the Labour manifesto planned to hammer both. But, again, the rationale for cutting corporation tax is not some deep-seated desire to help wealthy CEOs, but because taxes on business ultimately mean not just lower dividends, but lower wages and higher prices for consumers.

A failed free market?

Equally, Starmer’s contention that the ‘free market model has failed’ is plainly ridiculous. For one thing, the UK does not have a ‘free market model’, but a mixed economy in which government spending accounts for about 40% of GDP. There is scarcely an area of our economy that is not overseen by the state in the form or either tax or regulation. Ask a British economic liberal what they think of a free market economy, and they might well reply ‘it’s a great idea’.

And though Richard Burgon, Labour’s intellectual bellwether and would-be deputy leader, claims Boris Johnson is planning ‘Thatcherism 2.0’, in truth we have a Tory government committed to spending more on infrastructure and R&D, along with extra dosh for the health service, police and schools.

There is little in the Johnson prospectus to suggest we are about to see a dramatic paring back of the state, sweeping tax cuts or a bonfire of red tape (delightful though that might be). But it’s notable that where there are tax cuts, the PM is prioritising lightening the load for those on the lowest wages by raising the national insurance threshold – a policy championed by our parent organisation the Centre for Policy Studies.

Where there is a sense of radicalism, it’s in Dominic Cummings’ attempts to rewire the state to make it more responsive and efficient – if he succeeds that will be very welcome, but it seems more to do with making the state work better than with shrinking it.

A new model?

More interesting than these two-dimensional soundbites about the iniquities of liberal economics are what Mr Starmer’s own vision is for post-Corbyn Labour.

On the one hand, has a certain amount of leeway while the electorate is, frankly, not paying much attention to Labour. That means he can pitch hard to the left in the leadership battle – particularly if he wants to see off the Corbynite choice, Rebecca Long-Bailey.

Should he triumph, though, he will face an altogether harder question about what his version of Labour looks like. Does he have a coherent alternative to the ‘free market model’, or is it a toned down version of Corbyn’s outdated socialism, with the same old leftwing cocktail of nationalisation, higher taxes and ever more state intervention in the economy?

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.