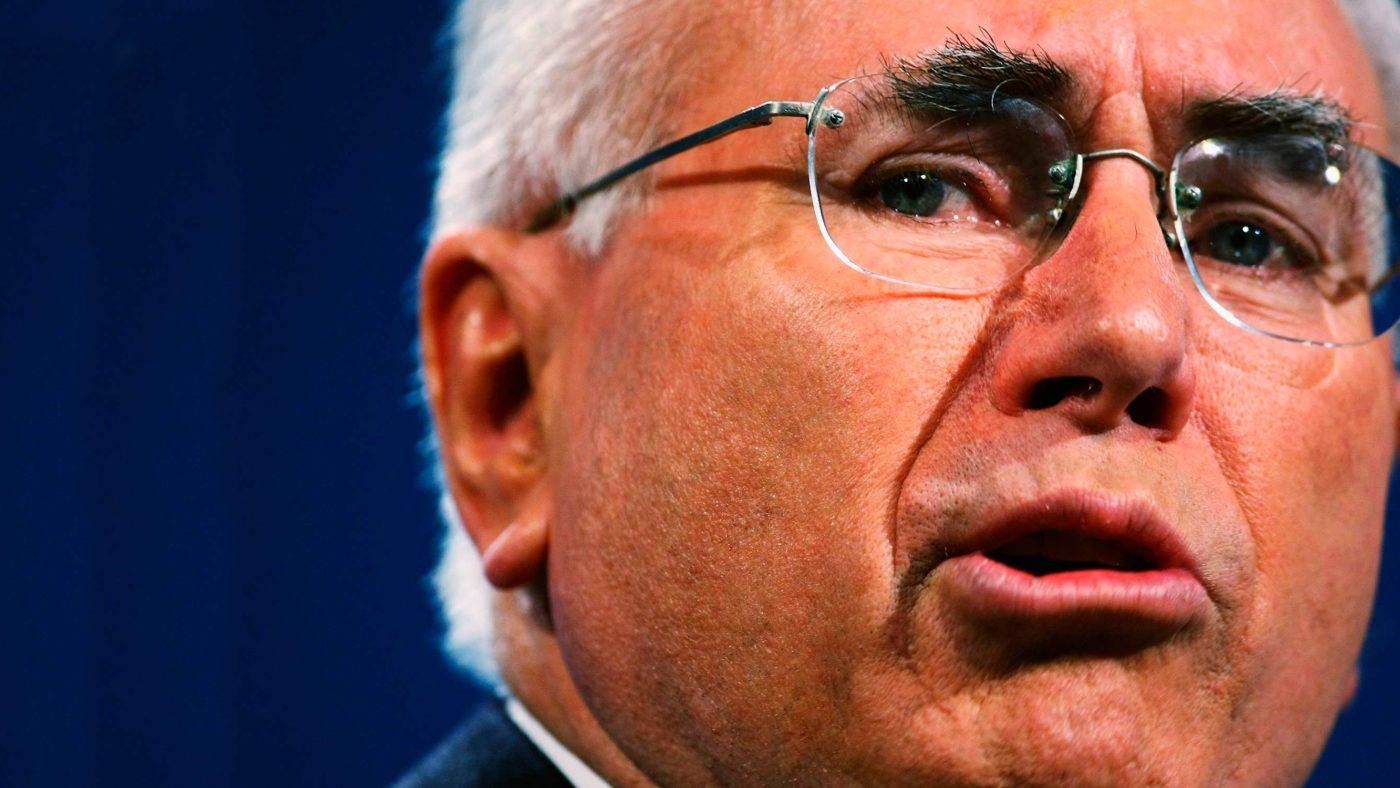

On November 1, the Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe presented the Edmund Burke Award to the John Howard in a ceremony at the National Gallery in London. The award recognised not just Howard’s four election victories, but his extraordinary accomplishments in promoting conservative ideals in Australia and beyond. This is an edited transcript of his speech.

We live in a time when – to use a biblical expression – there’s a lot of wailing and gnashing of teeth about the state of politics.

It’s occurring in all of our countries. It’s occurring in Great Britain. It’s occurring in Australia. It’s occurring in particular in the United States, as we face an extraordinary presidential election where the level of disenchantment with the two major candidates is quite unparalleled.

And in the shadow of this great man Edmund Burke, and conscious of the award that I’ve been given, I would like to briefly reflect on the relevance of some of the things that Burke said through his career on the state of politics.

The new swearword of the political commentariat is “populism”. If you’re not happy with something, then it’s a result of populism having won the day. And I can understand that. It’s easy to run a populist campaign. But it’s also easy to lose sight of the fact that we’ve always had populism.

There have always been people who are unhappy with the impact of particular political decisions on their lives, or on their communities. And it’s always more likely that that will be the case in the wake of more difficult global economic circumstances.

Yet I think as we wail and gnash our teeth about what we see as populism around the world, we shouldn’t lose sight of the fact that it has come on the heels of a period of time – between the early 2000s, or even earlier than that, through to the global financial crisis – when many of the governments and many of the communities of the Western world were pushing against an open door when it came to economic expansion and economic activity.

And it’s also easy to lose sight of the tremendous games that globalisation and competitive capitalism have brought to the world, not least the poor of the world.

I often hear of those on the Left saying the great moral challenge of our age is climate change. I think that’s nonsense. The great moral challenge of our age remains as it has been for many ages: the removal, through fair means of free-market-based growth, of the gap between the rich and the poor.

That’s the great moral challenge. And that is the methodology by which that gap should be closed. Not by state ownership and redistribution. But rather, by the fruits of competitive capitalism and globalisation.

We should never cease to remind the world – and remind our electorates – of what globalisation and what competitive capitalism has done for hundreds of millions of people lifted from absolute poverty in many parts of Asia and South America, and now increasingly in the continent of Africa.

That is the great success story of the last several decades. And whenever I hear the voices of criticism of globalisation and open trade, it distresses me immensely.

For example, both of the candidates in the United States appear to have turned their backs on the Trans-Pacific Trade Partnership. Something that would involve the economies of 60% of the world. Even though the United States has been so often the standard-bearer, the great clarion crier, when it comes to trade expansion and trade growth.

So let me say again, we should never lose sight of what globalisation and competitive capitalism have done for the poor of the world.

And Edmund Burke’s life reminds us – as does his example as a Member of Parliament – that politics, above everything else, is a battle of ideas. It is not a public relations contest.

When I think of those towering figures of world conservatism, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, we are instantaneously reminded that theirs were lives committed to the great battle of ideas.

When Ronald Reagan told his speechwriters that he was going to deliver a speech calling on Mr Gorbachev to tear down that wall, they shuffled their feet. Many of his foreign affairs advisors said well maybe it’s not quite the right time to say that. The Wall had been up for a few years by then. But he went ahead and he did it.

Reagan was an exemplar of a person who understood that at crucial moments in the history of his own nation, and of the world, there was a time to stand against any tide of nervous public opinion in favour of principle. As far as he was concerned, there was a great principle involved.

And we all know as a consequence, not just of that but of the special partnership forged between him and Margaret Thatcher, with a magnificent moral contribution of leadership from Pope John Paul II, that great product of the proud Holy State, we saw eventually the collapse of the Soviet Union.

And in your own country, of course, the example of Margaret Thatcher stands with equal height. There was never any doubt that she saw politics as a battle of values and ideas. There was never any doubt what her values and what her ideas were.

She wasn’t always right – nobody in politics is. But she got the big things right. And the successful political leaders of the world are those that get the big things right.

Political leaders who try as hard as they can never to make a mistake will never get any big things right. Because in the end, it’s getting the big things right that really matters.

Burke also reminded us – and Jesse Norman, his biographer, did tonight – of the importance of the political party as a core unit of advancement and activity.

And we shouldn’t, in reflection of that, feel in any way complacent about the state of party politics around the Western world.

Political movements today are not the mass movements they were 40 or 50 years ago. Their memberships are not as representative of the generality of the people who vote for them as they used to be. They are far more prone to falling into the hands of factional operators than used to be the case.

And it’s very important that we understand that we are dealing with an electorate that is more prone to approaches not based on principle, but on what I regard as the insidious rise of identity politics. Identity politics whereby you seek to gather the support of a group based on what that group has in common, not the support of that group for a common principle which might gain acceptance throughout the entire community. That is not a healthy development.

I think it’s also important to remind ourselves – and this is perhaps the one comment that I might make on your recent referendum on membership of the European Union – is that despite what we are frequently told by many, we still live in a world of the nation state. It is still a Westphalian world. It is still a world where the key organising principle of world affairs is relations between nations.

That is not a call to move away from international cooperation. It is simply a recognition of what the nation state can achieve.

As I’ve moved around the region in which my own country is geographically located, I’m constantly reminded of the great admiration held for Lee Kuan Yew, the founder of the state of Singapore. He is a classic modern example of somebody who recognised the power of the nation state, which is reflected in his ability to build this wonderful country from so little and in such adverse circumstances.

Finally, I think Burke would want us tonight to understand how fundamental to the sort of society he helped bequeath, to this and other generations, is the importance of defending free speech.

I’ve often argued – and it remains my very passionate view – that you don’t need a Bill of Rights. Bills of Rights restrict rights, they don’t expand them.

If you have a robust parliamentary system, if you have a completely free media, if you have an incorruptible judiciary, you’ve got the elements of a free society – you’ve got the basics.

But we do live in an age where there’s a creeping political correctness which is restricting free speech. I can think of two quite egregious examples of that, one in my own country and one in yours.

Recently, a well-known cartoonist in The Australian magazine, Bill Leak, published a brilliant cartoon which depicted an Aboriginal policeman holding an Aboriginal boy and confronting the father of that boy and saying to the father: “It’s about time you taught him about personal responsibility”. The father, holding a can of beer, said: “Righto, what’s his name then?”

It was a brilliant, perceptive cartoon, that made the point that failed fatherhood is a series problem – and I think it was a point that was applauded around the community, not just in relation to the Aboriginal community, where failed fatherhood is a problem, but other communities where the same is true.

And yet, for his pains, this man and his magazine were dragged before the human rights commission in Australia and asked to explain. That is a terrible assault on free speech. A terrible assault on free speech. Burke would be appalled – rightly so.

I think Burke would also be appalled about what I might loosely call the baker’s case in Northern Ireland. Where a baker has a view about same-sex marriage which he’s entitled to have, which other people don’t have, but that’s not the point. The point is he gets prosecuted for refusing to place a statement on the icing of a cake that does not reflect his own personal view. And the man ends up being dragged before the courts.

I don’t condemn the judge – the judge was enforcing his interpretation of the law. But if we really live in the shadow of Edmund Burke, and we revere him, and we value his principles, then surely we would look at those two examples of the way in which a creeping political correctness has spread, the manner by which any discrimination laws have been carried to almost demented lengths, and we would express our concern and our alarm at those developments.

Tonight is a special occasion for me. And I know I speak for my wife Janette in saying how moved we are to see so many old friends in the room, in the capital of a nation for which I have deep affection and which has contributed so much to the things that we hold dear – and through the centuries has stood against tyranny, supported always by my own country and by our friends in other parts of the world, particularly across the Atlantic.

And to say to all of you that the legacy of Burke is a precious one. It informs, as Daniel Hannan said, my own party, which I’ve always described as a broad church of classical liberals and conservatives. It’s a great heritage, and you have all in different ways fought to defend it. I thank you for that.

And in accepting this award with great gratitude, I want to salute Daniel, and you Jan [Zahradil, ACRE’s president] and your friends for the way in which you carry the torch for the right kind of conservatism: that great blend of preserving what is good until it is proved bad.

And for preserving too a fundamental belief in the importance of individuals; a belief in the need to limit the role of government; a faith in markets; and a belief in the right of people to accumulate private property, to make money, to be successful in life, providing you do it honestly and you pay through taxation – your due contribution to caring for those in the community who, through no fault of their own, have fallen through the cracks.

I know everybody in this room stands for that kind of society, and to the extent that I have helped in my own political life to build it in my own country, I’m grateful to have had the opportunity – and I warmly thank you for the honour you’ve done for me tonight. Thank you.