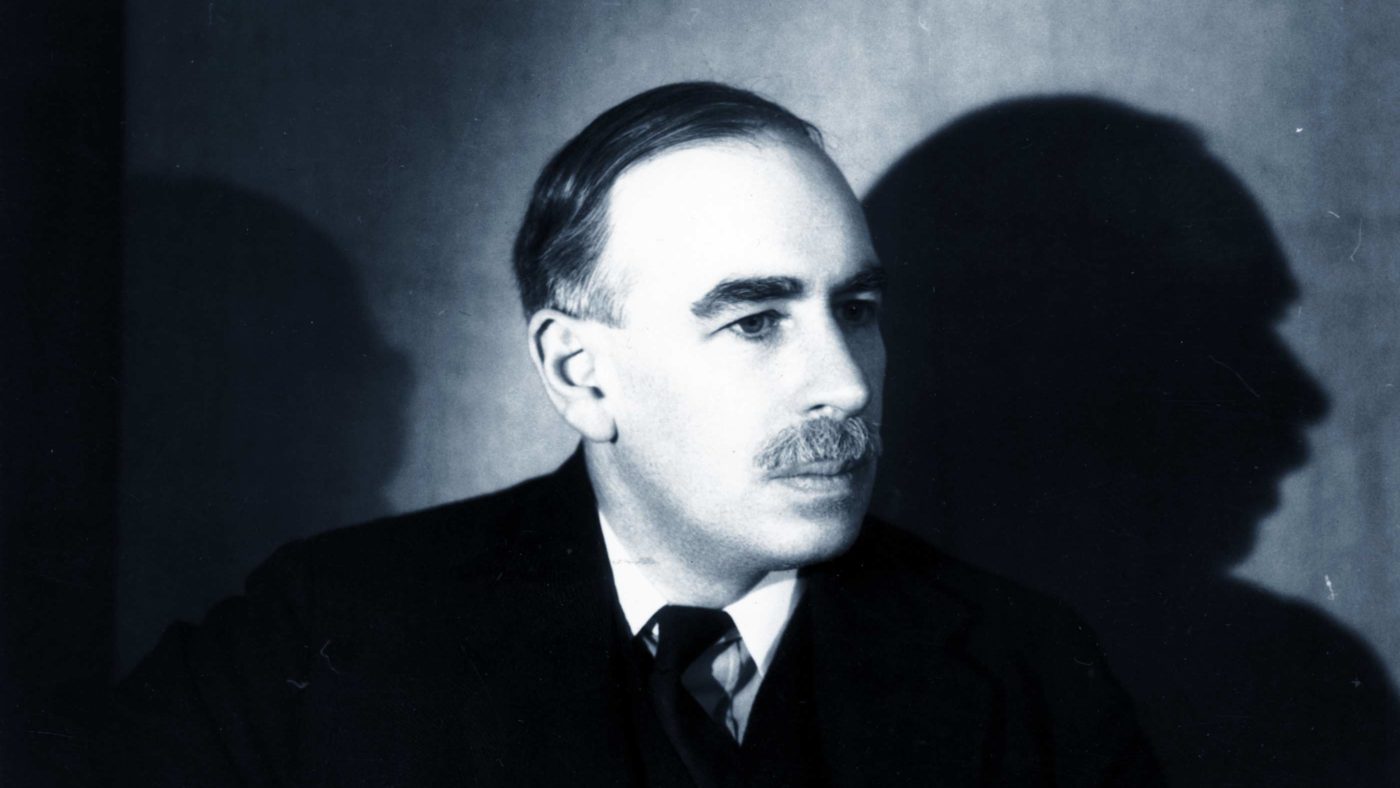

Given that even demi-God Gordon Brown failed to abolish boom and bust, it is worth putting some thought towards what economic policy should look like during the next recession. As Keynes pointed out, those animal spirits are going to mean a downturn at some point, so let’s work out what we’re going to do now rather than improvise when the time comes.

As ever, there are two policy areas in which we can deal with the macroeconomy: monetary and fiscal. The Bank of England’s former deputy governors now tell us that monetary policy will be maxed out next time. Yes, OK, we were told that last time too, monetary policy wouldn’t work at the zero interest rate bound and yet QE did just fine in stopping a depression. But, if we take the warning seriously, what should we do?

As they say, their warning leaves only fiscal policy, meaning that we must either increase spending or reduce taxation. Politicians will slaver at the idea of spending more of our hard earned cash. But what about doing the opposite? Why not boost the economy by leaving more money in our pockets? In fact, the lesson from the last recession is that this is the way to go.

There were plans to build all sorts of lovely infrastructure and yet nothing actually did happen, did it? President Obama had $800 billion to spend on shovel-ready projects and managed to finish nary a one. Train sets don’t work either. HS2 is still on the drawing board and likely still will be – if not righteously cancelled – the next recession but three. In reality, we’ve so lathered the economy with permissions and licences, inquiries and possible routes of objection, that no major government spending plan can actually move forward at any speed. Most certainly not at any speed that would alleviate the effects of a recession where we want things to be happening in a few months, not decades.

That leaves us with tax cuts. For don’t forget Keynes’s insight that it’s the difference between tax taken out and spending going in which stimulates the economy. We can mutter about the spending multiplier but that’s a marginal effect, more than offset by the manner in which spending doesn’t happen more than glacial speed.

The political optics of corporation tax cuts aren’t good. It’s also true that they would take quite some time to work through. Income tax cuts would work better, VAT again, but these aren’t quite the best.

There’s one tax which is taken out every paycheque, meaning that the maximum time for it to take effect is one month. That tax is national insurance. So, let’s cut national insurance in the next downturn.

We’ve got even more empirical evidence from the recent unpleasantness. It’s often said that temporary tax cuts will run into Ricardian Equivalence. They’ll make no difference as everyone will know that taxes will rise again to cover that bounty so they’ll save the cash to pay those future taxes.

Fortunately, the Americans tested this with there were two sets of tax cuts. One sent cheques for a few hundred dollars to most households and these were largely saved or paid down debt. Not what we’re looking for. Cuts in social security (the equivalent of national insurance) were spent as they were tens of dollars each week. Cumulatively they added up though. Stimulus through cutting national insurance contributions works. We get the rise in effective and aggregate demand, we don’t run into Ricardian Equivalence and it works quickly, something spending just doesn’t.

All of which presumably is why Keynes himself was converted to the idea by 1942. Thus this is what we should do next recession. Forget all those grand spending plans which won’t come to fruition in time to do any good. Cut national insurance so as to leave more cash to fructify in the pockets of the populace. It’s effective, timely, possible and works. The only people who will complain being those politicians who have far too healthy an interest in spending more of ours rather than less. To whom the correct answer is “Diddums”.