We live in an age of women’s progress. Or to be more precise, we live in an age when a number of long-term trends are paving the way for women, and particularly so young women, to climb the career ladder around the world. One such trend is that norms are changing. It is still common to find gender-biased attitudes wherein individuals are seen as less competent, reliable or valuable simply because they are women. However, over time, such attitudes have become less widespread, not least so in advanced market economies. Recent surveys for example find that the majority of Americans believe that women are every bit as capable of being corporate and political leaders as men. Many respond that women have advantages in terms of being organized and compassionate leaders. Such views are spreading around the world.

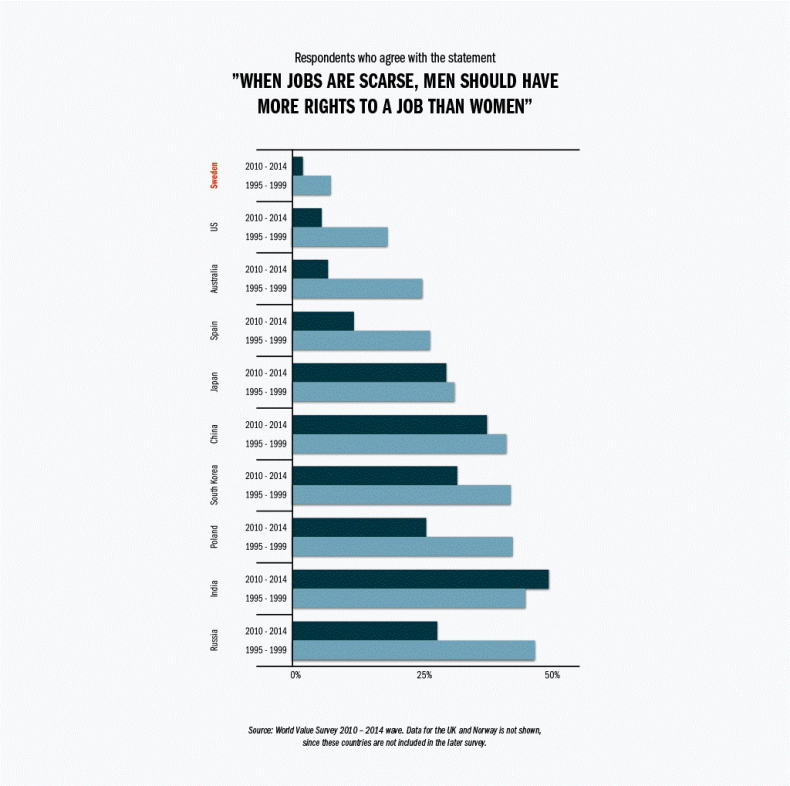

This change in gender attitudes is captured by the World Value Survey, an ambitious project that studies people’s perceptions around the world. Gender equal values have become more widespread over time in most countries. As shown below, the greatest change has occurred in countries that had gender equal values to begin with – such as Sweden, the US and Australia.

Alongside the change in attitudes, another key trend which promotes gender equality is urbanization. An increasing share of the global population has over time moved from the country side and smaller communities to larger cities. Urbanization affects women’s career opportunities since modern city life has great emphasis on individualism. City dwellers typically get married and have children later than those living in less densely populated areas. Women, who as a group are often held back by the responsibility for family and children, have the opportunity in urban areas to kick-start their careers before forming families. Much like tv-series like Sex and the City and Girls portray, city-life promotes gender equality in the modern economy. Of course, there is also an interaction between urbanity and values: in cities gender discriminatory views tend to be less common than in rural places. Metropolitan areas act like magnets, attracting young ambitious men. The pull-factor is even greater for young ambitious women.

So when will women finally be allowed to break the glass ceiling? When will the ruthless companies stop discriminating them? When will the capitalist system finally be open to women?

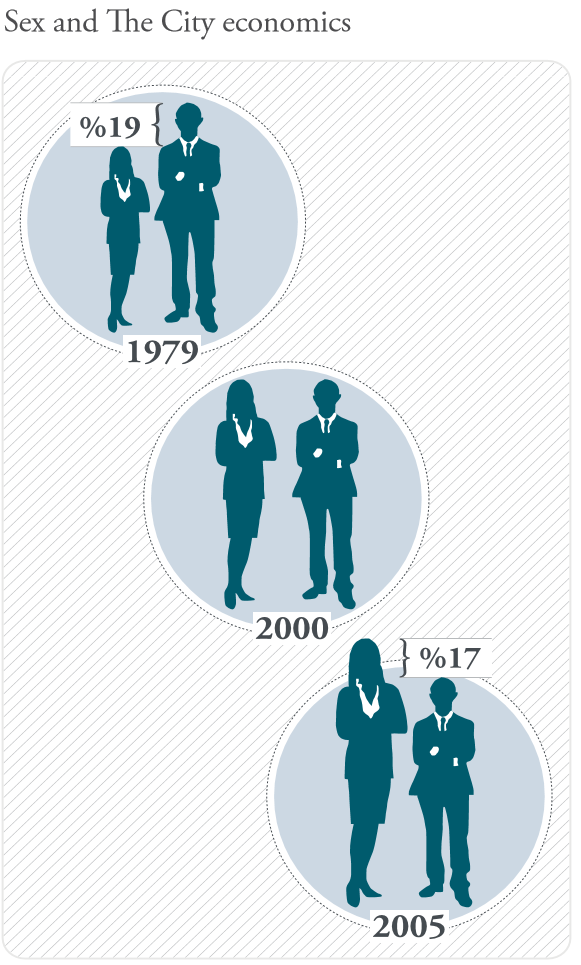

In part, this has already happened. Andrew Beveridge gained quite some attention a few years ago when he looked at the wages of young singles in American cities. When comparing 21 to 30 year olds in New York City, he found that a wage gap of fully 19 per cent had existed in favor of the women in 1979. By the turn of the millennium however, the young women had caught up. Five years later, the wage gap was again visible – but this time to the advantage of the women, who earned 17 per cent more. Another study has shown that young single women in most major US cities outearn young single men. Similar trends are found in the UK. The Guardian has for example reported: “Women in their 20s have reversed the gender pay gap”, as women between the ages of 22 and 29 typically earn £1,111 more per annum than their male counterparts.

The gender wage gap is a very real thing around the world. Women on average tend to spend more time taking care of children and family than men, investing less time in their careers. Also, women tend to work in fields which are less financially rewarding than those that men are attracted to. Large welfare states create even more problems, by creating public monopolies in the sectors in which women tend to work (healthcare, elderly care and education). However, the gender wage gap seems to be small or even reversed for young women in competitive private sector professions.

Jaison R. Abel and Richard Deitz for example explain:

“We often hear that women earn ‘77 cents on the dollar’ compared with men. However, the gender pay gap among recent college graduates is actually much smaller than this figure suggests. We estimate that among recent college graduates, women earn roughly 97 cents on the dollar compared with men who have the same college major and perform the same jobs. Moreover, what may be surprising is that at the start of their careers, women actually out-earn men by a substantial margin for a number of college majors.”

The young women who are today breaking the glass ceiling might fall behind their male counterparts later in life – if they start spending more time on housework and less on market work as they form families. Still, it is encouraging to know that the glass ceiling is not impossible to break. In fact, signs that young women are breaking the glass ceiling can be found even in unexpected places, such as Iran. Although many social and political obstacles stand in their way, young women have begun to dominate higher education in Iran, even traditionally male-dominated fields such as technology. Forbes has for example reported

“70% of Iran’s science and engineering students are women, and in a small, but promising community of startups, they’re being encouraged to play an even bigger role.”

We will likely see more young women breaking the glass ceiling, in more parts of the world, in the years to come.

The main question is how economies can adapt, so that young women who have top careers don’t fall behind their male peers later in life. As I show in the Nordic Gender Equality Paradox, part of the answer is policies, such as low taxes on services and affordable child care, which make it possible for parents to combine family and work. Another is competitive markets. Some individuals or even firms might be inclined to discriminate. But the more competition that exists, the more will companies that hire based on merits rise above their competitors. Individuals and firms in competitive economies find that discrimination often is a loss for the person discriminating as well as the one being discriminated. Market competition is an often forgotten force that, together with urbanization and changing norms, hopefully can continue to pave the way for women’s success.